How a newspaper stood up against the February 23, 1981 coup

New film tells how EL PAÍS created its historic edition after Civil Guards occupied Congress

On Monday, February 23, 1981, Daniel Gavela was off duty. The then deputy editor of the national desk at EL PAÍS had an appointment at 6.30pm at Plaza de las Cortes in Madrid. But when he got there, he found the entire area cordoned off.

Realizing that something serious was going on, he phoned the newsroom, hailed a cab and sped back to his desk. The taxi driver had the radio on and state broadcaster Radio Nacional was playing military marches.

“This may be the last thing I do as editor-in-chief, but the newspaper is going to go out on the streets with an editorial against the coup plotters”

“It was like going back through a dark tunnel of history,” he recalls.

At 6.23pm, Lieutenant Colonel Antonio Tejero had stormed Congress gun in hand, interrupting the plenary session that was due to vote in Leopoldo Calvo-Sotelo as Spain’s new prime minister.

Tejero had around 200 armed members of the Civil Guard with him.

A special program on the 23-F coup

EL PAÍS Video will be airing a special program about the newspaper's experience of the February 23, 1981 (23-F) coup on Tuesday night from 9pm. The program includes a showing of El País, con la Constitución, a new documentary featuring first-hand accounts by the journalists who produced the special edition of EL PAÍS that night, led by then editor-in-chief Juan Luis Cebrián, who is now the CEO of the Prisa Group, the paper's parent company.

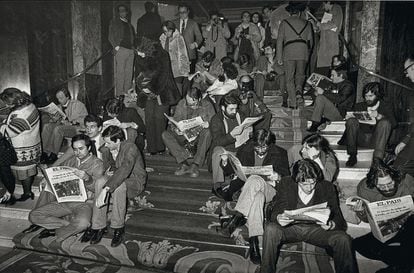

The documentary received its big-screen premiere on Monday night at the Capitol theater in Madrid.

The program is part of the EL PAÍS digital edition's new emphasis on self-produced audiovisual material. On November 30, the website aired the first ever election debate between the candidates for prime minister designed for the internet following a television format.

At that precise moment, editor-in-chief Juan Luis Cebrián – now the CEO of the Prisa Group, the parent company of EL PAÍS – was in his office interviewing a candidate for a reporter’s position.

Suddenly he got a call from his deputy, Augusto Delkáder, who told him to turn up the radio. He had just heard the famous words by Tejero: “¡Quieto todo el mundo!” (Nobody move!).

Cebrián and Delkáder were unable to see most of the deputies scrambling under their desks. But they did hear the shots from Tejero’s gun.

No doubt it was a coup attempt, and the newspaper was immediately faced with a dilemma: should EL PAÍS go to print or not?

“If the coup was successful, the newspaper would be a sure victim. I thought our only line of defense was the newspaper,” recalls Cebrián in the documentary El País, con la Constitución (El País, with the constitution), which was produced by Prisa Video and premiered on Monday at Madrid’s Capitol movie theater.

The film follows the making of that historic issue of EL PAÍS, dated February 23, 1981, from its inception to its delivery to the doors of Congress.

Eduardo San Martín, the then desk chief, sat at several decisive meetings held that day.

“The editor-in-chief called the union and company representatives because it was all about providing an institutional response to the event, not about a bunch of mad journalists storming the streets to fight gun-toting individuals with newsprint,” he recalls.

Delkáder still recalls Cebrián’s words at the time: “This may be the last thing I do as editor-in-chief, but the newspaper is going to go out on the streets with an editorial against the coup plotters.”

Two hours later, a 16-page special edition came out with a size 72 font headline (twice the regular size at the time) that shook readers: “Coup d’etat. EL PAÍS, with the Constitution.”

It was the first of seven editions that EL PAÍS produced between the afternoon of February 23 and the early hours of February 24.

It was also the first daily to run the story of the February 23, 1981 coup – known as 23-F in Spain – with a clear editorial backing the Spanish Constitution.

“In my opinion, 23-F was the most important moment for EL PAÍS in its entire history,” says Soledad Álvarez-Coto, who was the head of the national desk in charge of organizing coverage inside and outside the newsroom.

Álvarez-Coto, who played a key role in that special edition, is one of 40 people who participated in the film project, which also include writers and photographers (several of whom, such as Marisa Flórez, Miguel Ángel Aguilar and Bonifacio de la Cuadra, were inside Congress at the time of the failed coup).

Desk chiefs, managers and Civil Guards also contributed direct testimony to a documentary that creates a unique narrative of that day, and provides an inside look at how that historic newspaper edition came to life.

“We wanted the documentary to follow the special edition of EL PAÍS, respecting all the chronological steps: the presses, the newsroom, the streets of Madrid, the Palace hotel, Congress and so on,” explains María José Díez, the director of the production.

Historical documents play a special role in the film. “Early on during the production stage we realized that we didn’t need that much archive material because the characters were telling such an incredibly interesting story. It seems like we already know everything about 23-F, but we found a story that nobody had talked about or written in the first person,” says Díez.

“We didn’t want to make a scientific documentary. We wanted to create a believable version based on the memories of the main participants,” adds Maruxa Ruiz del Árbol, a member of the 12-person team who made the documentary a reality.

The newspaper came out at 9pm, when the newsstands were already closed. But groups of volunteers from the press and advertising departments distributed it throughout the city. But even that was not enough.

“We need to get it inside Congress so Tejero will see that this is not going to be so easy,” thought Cebrián. Manolo de la Rica, then the advertising director, managed the feat.

The newspaper was like a breath of fresh air inside Congress.

“My moment of greatest satisfaction, in the middle of so much anguish, was when I went to the bathroom,” recalls the Socialist politician José Bono, who was then fourth secretary in Congress.

In the hallway, there was a Civil Guard sitting reading a newspaper and, as I was passing by, he gestured to me in what I construed to be a friendly way, and closed the newspaper. I saw the front page; it was EL PAÍS, and it said something like ‘The coup has failed.’ I forgot all about peeing.

“I went back and told Landelina [Lavilla, the congressional speaker in 1981]: ‘Landelina, these guys have lost, I read it in the newspaper.’ Being reunited with EL PAÍS on paper was like identifying with democratic Spain.”

English version by Susana Urra.